How the nervous system uses consciousness

You are a conscious interlock and an animal that gets hit with a stick

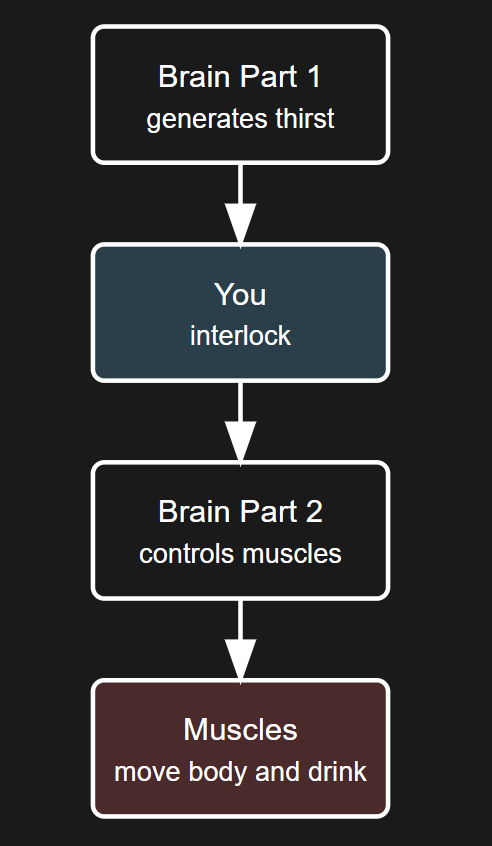

Let’s take a careful look at a simple example.

You’re sitting at your desk answering email when you notice you feel thirsty. You rise from your chair, walk to the sink, fill a glass of water, and drink. You feel a pleasant feeling of relief.

What happened under the hood?

Your brain decided that your body needed more water, so it generated a sensation of thirst.

To alleviate this unpleasant sensation, you commanded your brain to walk to the sink and drink water.

To execute your command, your brain commanded your muscles to walk to the sink and drink water, and they did.

The brain rewarded you by generating a pleasant feeling.

This is what engineers call a control chain. As I’ll explain in a moment, your role in this chain is what they call an interlock.

In earlier drafts of this article I put “you” in quotation marks throughout the text to indicate that we don’t know what “you” is or the extent to which it’s an illusion. But the marks clutter up the text so I’m replacing them with this paragraph. What we do know is that there’s something that reacts to thirst and causes the body to act, otherwise the existence of thirst make no sense. I’ll call it “you” because I’m addressing you in this article and it feels like what you call “I”. I don’t mean to imply that it’s not brain activity or that it’s distinct from “Brain Part 2” on the diagram above. I made the second and third boxes separate in the diagram only to allow the possibility that those things are distinct. You can think of the word “you” in this article as a variable name in an equation.

What that “you” is, really, is one of the greatest questions that have ever been raised. This is the first article on this blog and we have plenty of articles ahead of us to ponder it. For now, I’ll just write “you” and ask you to remember that I’m asserting very little about its nature or implementation.

Getting back to our example, your trip to the sink to drink water, your brain controlled you by making you thirsty. It used this method because you’re conscious. You are capable of feeling thirst and disliking the feeling. You’re the only conscious component in the control chain.

You have no control over the parts of the brain that are active in step 1 — if you did you could turn off the unpleasant feeling of thirst — but you do control the parts of the brain that are active in step 2.

Why is the chain constructed this way? Why don’t the step 1 parts of the brain directly command the step 2 parts of the brain?

Because those parts of the brain lack judgment. They act mechanically.

You are there as an interlock, as a component that can suspend the commanded action. You can do this because you are not only conscious but intelligent.

Suppose for example that the brain issues a command to drink (i.e., makes you thirsty) at a time when a lion is snoozing next to the stream. You will see the lion and decide not to drink even though you’re thirsty. If you weren’t in the chain, your body might walk to the stream and get killed.

You have the power to override the brain’s command but you can’t do so lightly because because you can’t stop the unpleasant thirst it makes you feel. Therefore you will override its commands only when the stakes are high. Moreover, there’s a time element built into this mechanism: the longer you wait to comply with the brain’s command, the more intense the thirst becomes and the harder to resist it.

It’s a very clever design. Natural selection is a very clever designer.

Carrot and Stick

Let’s see what else we can notice about this design.

As noted, the step-1 parts of the brain force you to act by making you feel bad. This is like a rider hitting a horse with a stick to make it run. After the body drinks, some parts of the brain, maybe the ones that are active in step 1, give you a pleasant feeling of relief. This is like a trainer rewarding an animal with food for doing what the trainer wants. This is a carrot and stick mechanism, and you are the animal.

The nervous system uses sticks and carrots for many other intended purposes. It’s a general pattern. Some examples:

Hunger to make us eat

Horniness to make us reproduce

Fear to make us hide, flee, or fight

You

I keep saying "you" but is it really you? What do we actually know about this you?

We know two things: (1) It's conscious, otherwise it couldn't feel thirst or relief and the mechanism wouldn't work. (2) We know it can control the body's movements, otherwise it wouldn't be able to command the brain to operate the muscles.

Objections

Objection: This mechanism is illusory. The brain generates an illusion of an entity that feels thirst and reacts by controlling the muscles.

Reply: If the mechanism is illusory, why does it include thirst and relief? How could natural selection know it should design the illusion to resemble a carrot-and-stick mechanism? It has no way to know that if you had the two numbered characteristics specified above, you would act as you appear to act. And even if natural selection had that knowledge, it has no way to impose the design on organisms. For this reason, I don't think this objection is plausible.

Objection: You're taking this "mechanism" too seriously. At best it's a naive model — and calling it a "model" is generous — and you're reifying the hypothesized components.

Reply: Thirst is not a hypothesis or a model. If you've never been extremely thirsty, you might find it interesting to go without water for 36 hours and see how hypothetical it is. On second thought, don't — that would be dangerous. To this undeniably real element I've added the hypothesis that it's generated by the brain, which I don't think anyone here doubts, and the hypothesis that something ("you") reacts by causing the body to perform certain actions. Those actions are of course beyond doubt. The only part of this that seems questionable to me is the hypothetical "you" that reacts to thirst by causing the body to move. If there isn't some sort of "you" that behaves as I've suggested, there's no explanation for the rest of the chain that I can think of. If you can give me an alternative hypothesis for this chain of events I'm all ears.

Conclusion

I’ve tossed out a lot of ideas in this article but I wrote it mainly to point out three facts which I’ll build on in future articles.

The carrot-and-stick aspect of the mechanism relies on consciousness without thinking.

The interlock aspect of the mechanism incorporates both consciousness and thinking.

The mechanism serves a basic physiological need, seeking and drinking water to prevent dehydration, which is at least as old as the earliest land animals. That’s a few hundred million years.

Bonus Chatter

Advaita Vedanta, the most prestigious school of Hindu philosophy, claims that doership (kartṛtva), the feeling we have that we perform actions, and the ego (ahaṅkāra), the feeling we have that we are individual I’s inside our bodies, are both illusions.

A reminder: when I refer to “you” in the control chain, I’m talking about the entity you call “I” from your own point of view.

If what I wrote above is correct, this “you” is a pretty solid illusion. It has a causal role in the control chain. Isn’t that a doer? When we say “I’m thirsty” this “you” must really be what feels thirsty, otherwise it can’t perform its role in the control chain. Isn’t that the ego? If this “you” is an illusion how come we’re not all dead from dehydration? Advaitins might reply that it’s an illusion in the sense that it seems to be separate from Brahman yet have the characteristics of Brahman. If so, fair enough.